metro

Whoever has not discovered this truth about the fragility of our journey, and the pervasive power of our necessary adaptations to this vulnerability, is living in a form of self-delusion that psyche, fate, or the consequences of our acts will sooner or later bring to the surface. What we do then will make all the difference in the rewriting of history. None of us is pleased to encounter the false self, the necessary fictions in which we invest, until even we can no longer believe them. Naturally, we will avoid these unpleasant truths as long as possible, and will enter a deepened dialogue with ourselves only when exhaustion or failure or disorientation is no longer deniable. But our long-delayed appointments with the soul are meant to be taken seriously, and treasured, for the level of consciousness we bring to such moments will make all the difference for the rest of our lives-for ourselves and for our loved ones.

James Hollis from Finding Meaning in The Second Half of Life

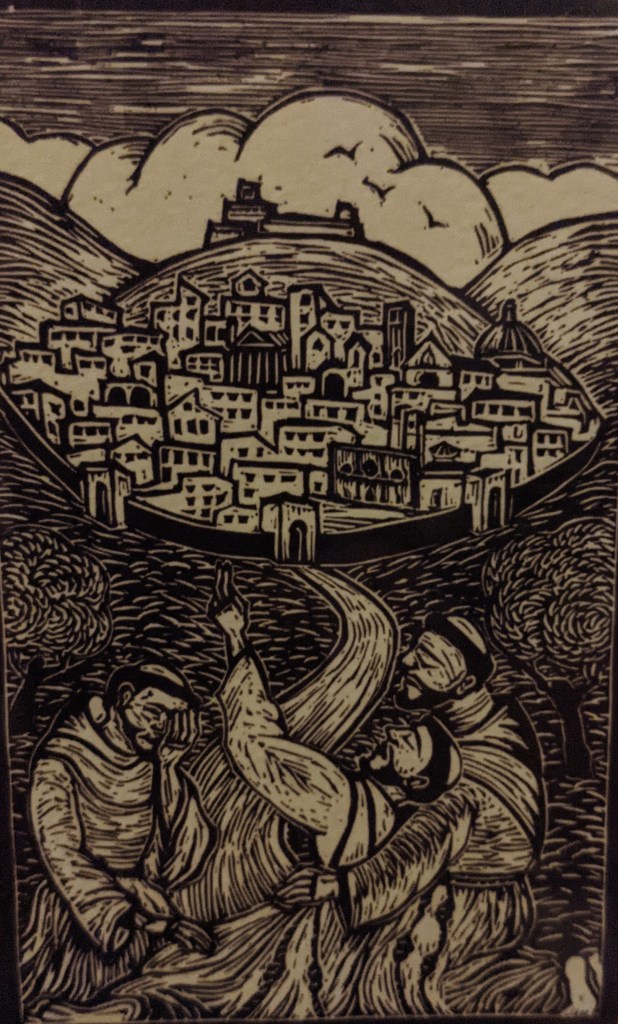

This evening, followers of St. Francis of Assisi will keep a memorial of his passing on October 3, 1226. I pray that his spirit of reconciliation and love for all creation bless each one of us.

Blessing of St. Francis –

May God bless you and keep you, smiling graciously on you, granting mercy and peace,

granting mercy and peace. May God bless you and keep you, May you see the face of

God, granting mercy and peace, granting mercy and peace. Amen. Amen. Amen

Christian Wiman – Our minds are constantly trying to bring God down to our level rather than letting him lift us into levels of which we were not previously capable. This is as true in life as it is in art. Thus we love within the lines that experience has drawn for us, we create out of impulses that are familiar and, if we were honest with ourselves, exhausted. What might it mean to be drawn into meanings that, in some profound and necessary sense, shatter us? This is what it means to love. This is what it should mean to write one more poem. The inner and outer urgency of it, the mysterious and confused agency of it. All love abhors habit, and poetry is a species of love.

It is instead a question of aligning one’s intention with the God within and with us, through love and in grace. To make the alignment possible, Jesus proclaimed a message of radical forgiveness, not only forgiveness of humanity by God, but also forgiveness of one another by people. In this radical forgiveness, it is even possible to be freed of attachment to one’s own guilt for or justification of the wounds one has inflicted upon others. True love of self, a reverence for the essential goodness of God’s creation, is made possible. Herein lies the potential for endless freedom in the service of love. Nothing, not even one’s own sinfulness, has to remain an obstacle to the two great commandments.

Gerald May, from Addiction and Grace

This is the contemplative option-not any system of complicated exercises, but the simple and courageous attempt to bear as much as one can of reality just as it is. To be contemplative, then, is not to be a special kind of person. Contemplation is simply trying to face life in a truly undefended and open-eyed way.

– Gerald May, from Addiction and Grace

We must not lose hope: God is always and forever at work in the soul and in history. Even this secular world continues to produce mystics and saints.

Men and women are still falling in love with God, especially after they realize how much God has loved them when they were unlovable—and how God trusted them when they could not trust themselves, and how God forgave them when they could not forgive themselves. Be honest, what else would make you fall in love with God?

Authentic freedom and love will not be captured by attachment. Therefore, the journey homeward does not lead toward new, more sophisticated addictions. If it is truly homeward, it leads toward liberation from addiction altogether. Obviously, it is a lifelong process…

There is a strange sadness in this growing freedom. Our souls may have been scarred by the chains with which our addictions have bound us, but at least they were familiar chains. We were used to them. And as they loosen, we are likely to feel a vague sense of loss. The things to which we were addicted may still be with us, but we no longer give them the ultimate importance we once did. We are like caged animals beginning to experience freedom, and there is something we miss about the cage.

Like the Israelites in the exodus, we know we do not want to go back to imprisonment, and we sense we are moving on to a better existence, but still we must mourn the loss of the life we had known. This is a poignant grief, yet somehow soft and gentle. With time, it will grow into compassion: compassion for the spiritual imprisonment of our sisters and brothers, and compassion for the many parts of ourselves that still remain in the chains of addiction. Grief and compassion are part of spiritual growth, the homeward pilgrimage from imprisonment to freedom, the homemaking of deepening love.

Gerald May from Addiction and Grace